by Lesley Evans Ogden

On November 19th, the Canadian Journalism Foundation held a webinar hosted by CBC journalist Anna Maria Tremonti, focusing on the mental health risk and injury of reporting on COVID-19.

The webinar discussed the results of a recent study initiated when Meera Selva, director of the journalist fellowship programme at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism in Oxford, England, began collaborating with Dr. Anthony Feinstein, professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto.

Their aim was to take the psychological pulse of journalists around the world reporting on COVID-19. Their early findings indicate that anxiety is affecting 25% of the journalists studied, with rates of depression at 20% and overall emotional and psychological distress in excess of 80%.

Feinstein underlined that help is available and there are ways for journalists to boost their resiliency. His list of mental health tips is available here and a condensed summary of the webinar discussion follows.

The joint Reuters Institute and University of Toronto study, which began in the spring of 2020, collected data from two large international news organizations, reaching out to a sample of 73 journalists.

The two media organizations, explains Selva, cannot be named since the study guaranteed anonymity to the organizations and participants. The journalists contacted for the English-language survey were those reporting directly on COVID-19 and were based in Southern Africa, Asia, North America and Europe. Journalists surveyed were asked to answer a set of questions on their working conditions and emotional state.

The study grew out of Selva’s concern in the late spring of 2020 about the “utter confusion” she was seeing in journalism. Journalists had been suddenly told to work from home, but were also being asked to cover potentially dangerous situations.

“The front line of journalism had changed,” says Selva, whose work at the Reuters Institute investigates press freedom, media diversity and journalists' well-being. “Suddenly, everybody was covering a potentially dangerous situation without really knowing if they themselves were vulnerable, and without having the network and the support of the news rooms that they normally have,” says Selva.

Journalists going into a war zone normally have protective equipment like a flak jacket. In this case, journalists were trying to do their job covering the biggest story of our age without any guidelines and under tremendous pressure.

Feinstein, a neuropsychiatrist who has previously studied how journalists are impacted by traumatic events, said the study had an excellent response rate.

“Two thirds of the journalists we approached wanted to take part,” he says. That means the data collected are likely representative of a broader group.

These were journalists covering COVID-19 in various ways – some going into hospital emergency departments and intensive care units, interviewing people that survived and relatives of people lost to the disease.

Asked by Tremonti what he found most concerning and surprising, Feinstein explained that “25% of our sample were anxious,” which is a very high number and a figure that overlaps with data collected from first responders during the pandemic, like doctors and nurses and health specialists.

“There’s a real similarity in this data,” he says. With 20% of journalists surveyed experiencing significant depression, that is very high as well. “Depression and anxiety often overlap,” says Feinstein, making it harder to treat.

On a more optimistic note, he explains, the news organizations surveyed were offering therapy to journalists, and 52% of the sample were using it. That, says Feinstein, represents “a sea change.”

Those who were receiving psychotherapy had less anxiety, less depression and less overall psychological distress, benefits that were seen in real time. The earlier you intervene, the better the result, he explains. Feinstein has created a tip sheet for journalists entitled Looking after your mental health during COVID-19.

One of the many challenges facing journalists covering COVID-19 is that it’s what Tremonti called a “fast moving, unrelenting story.”

Many journalists surveyed who were reporting on the pandemic felt overwhelmed. “No matter how hard they tried, there was always more work to be done,” Feinstein says. Many journalists surveyed, says Feinstein, internalized this as a moral failure -- that at this critical moment in society, they had fallen short.

“That was a false belief, a false perception,” he says, “but a reflection of them simply being overwhelmed by the magnitude of the task at hand.”

Meera Selva emphasizes that more women than men responded to the survey, and that data from women parallels that seen in society at large, reflecting the “time poverty” experienced by women.

“More women than men were showing signs of PTSD, anxiety and depression compared to the men,” says Selva. She underlines abundant data from multiple sources suggesting that during the pandemic, a disproportionate burden of unpaid work like childcare and helping children with online schooling is falling on women.

Asked to identify areas in which journalists can help themselves and help each other in terms of resilience, Feinstein emphasizes that in a time when we’ve lost control of so many things, we need to focus on the things we can control.

We can’t control the pandemic, the mortality rate, the economic news, the stock market, or the behaviour of fellow citizens.

“If you focus on that repeatedly you use up your resources of emotion,” he says. Instead, put your energies into things you can control. They're small, but cumulatively they make a difference.

Dr. Feinstein’s self-care tips and challenges

Try and step back from the intensity of the news story. Look after your sleep.

Watch what you eat. People tend to “comfort eat” when they are feeling stressed.

Devote a little bit of time for exercise. If you haven’t exercised in the past, start doing it now.

Most importantly, devote time and energy to your relationships. Stay in contact with people. With all the social distancing, and the bureaus closed, make a concerted effort to maintain those social contacts because they are protective from a mental health perspective.

And, attributing this piece of advice to a letter to the editor at the New Yorker by Kyra Morris, Feinstein underlines the idea that at a time like this, respite is a form of resilience. “I think that's key,” he says, and it’s become a mantra he uses for his journalist patients.

Step back from the intensity of the moment and look after yourself. Put into place in your day to day life those moments that nourish you, whether it's going for a walk, listening to music, doing exercise or maintaining contact with people. Mindfulness based therapy can be so important and helpful in a time like this. But have your moments of respite because you're in this for the long haul. You need your endurance.

“Journalists are very bad at this,” he says. “They have this tremendous work ethic, they just go-go-go, but they tend to neglect themselves... If you don't focus on yourself, you run the risk of burnout and using up your finite resources of emotional energy.”

Another challenge, he underlines, is the unwillingness of journalists to ask for help. He notes that there is often a belief, and a sense of guilt, that they should not ask for help because they are not as badly off as the people they are reporting on.

That’s a false belief system that prevents getting help. He likens this to breaking a leg, going to the emergency room, and seeing that person in the bed next to you has broken two legs.

“Do you get up and hobble out? Of course not. You stay there and get your treatment. And it's the same with mental health issues,” says Feinstein.

What you may be feeling will be a lot less than someone who has lost a relative. But it doesn't negate your emotions. If your distress is affecting your relationships or impeding your ability to work, reach out for help. Because it makes a very real difference.

Also, he advises, look out for other people. “Stay in touch with your neighbours. Don't lose touch with your elderly parents. Maintain these contacts, give emotionally to these people as well because that's helpful to you. But when it comes to dealing with all these forces that are swirling around in society right now, record them, note them, document them, try to understand the causes, but don't try to change them because you won’t,” he says.

Another reason journalists are under such strain in their mental health is because they are being accused of being peddlers of fake news, “which hurts when your entire profession is about telling the truth,” says Selva.

With politicians whipping up hatred against journalists and concerns about angry mobs, this is a very real issue. Other forms of attack, especially for female journalists, are the trolling and highly sexualized attacks online. Selva says it’s important to be aware that this is an issue and also a problem that you can seek help for.

She also suggests taking time to switch off social media for a while and not engage with it. “It’s important to give yourself permission to do that,” she says.

Freelance journalists, they noted, tend to work in even greater isolation, and Feinstein suggested supporting and staying in touch with colleagues via monthly meetings or calls, and trying mindfulness-based apps for anxiety and stress reduction.

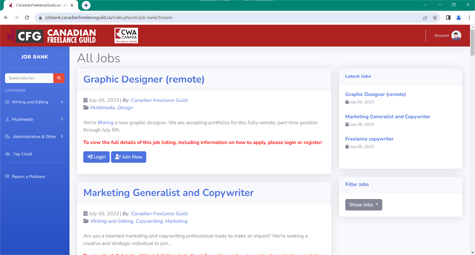

The panelists also flagged resources specifically available for freelance journalists including the Canadian Freelance Guild, Rory Peck Trust and Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma.

- Watch the show (starts at about 28 minutes)

- Listen to the podcast

- View the tip sheet Looking after your mental health during COVID-19, courtesy of Dr. Anthony Feinstein

- From the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism:

- COVID-19 is hurting journalists’ mental health. News outlets should help them now

Lesley Evans Ogden is a BC-based multimedia freelance science journalist. Check out samples of her recent work here and on her website, and follow her on Twitter @ljevanso.